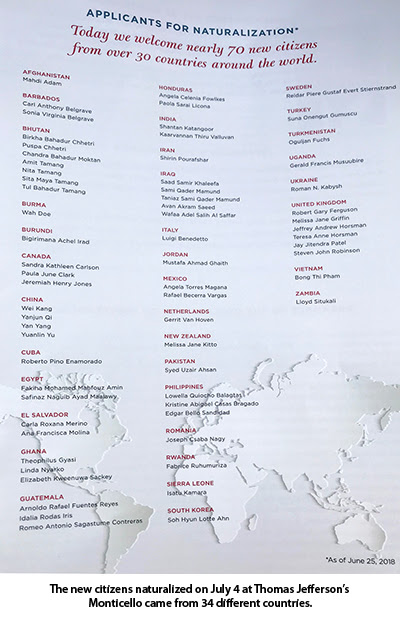

Almost every year since I arrived in Charlottesville in 1981, my wife Nancy and I have attended the annual July 4th naturalization ceremony at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Last week, another 67 people born in countries as diverse as Iraq and Ghana took the oath of U.S. citizenship, pledging to protect and defend our Constitution, and also renouncing “all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty….” Over the years, we have heard thoughtful or insightful speeches discussing Jefferson and his role in the founding of the country, and celebrating countless people from foreign shores who decided to take the oath and become American citizens. It is among the most inspiring events that an American can attend, largely because it links the power of Jefferson’s words with the promise of so many seeking a better life.

This week continued with two other significant events in Charlottesville, one to memorialize and remember the horrific lynching of John Henry James in 1898 as part of the Charlottesville Pilgrimage for Justice, and the following day, the LatinX picnic and Harmonia music benefit for migrant families in our area. Placing these alongside the Monticello celebration draws attention to critical fissures in our society and the work of citizens to address them.

The naturalization ceremony at Monticello has been occurring since 1963, and for the last thirty years, former Virginia Supreme Court Chief Justice John Charles Thomas has delivered a stirring reading of the Declaration of Independence to the assembled crowd. There is a certain ironic poignancy to Thomas’s reading; after all, Jefferson’s words at the time did not apply to African Americans like Thomas, and certainly not to slaves. The Declaration also did not apply to women, people who did not own property, and Native Americans. Jefferson’s words, penned at the age of 33, remind us how idealistic a country we are. But locating them in historical context also underscores that while we have traveled a substantial distance, we still have a long way to go in order to become a “more perfect union.”

has been occurring since 1963, and for the last thirty years, former Virginia Supreme Court Chief Justice John Charles Thomas has delivered a stirring reading of the Declaration of Independence to the assembled crowd. There is a certain ironic poignancy to Thomas’s reading; after all, Jefferson’s words at the time did not apply to African Americans like Thomas, and certainly not to slaves. The Declaration also did not apply to women, people who did not own property, and Native Americans. Jefferson’s words, penned at the age of 33, remind us how idealistic a country we are. But locating them in historical context also underscores that while we have traveled a substantial distance, we still have a long way to go in order to become a “more perfect union.”

The character of the naturalization ceremony has changed dramatically over the years, as Monticello has become increasingly sensitized to the role of slavery in the creation of our nation, and to the relationship between Jefferson and his slave, Sally Hemings. Nonetheless, the words of the Declaration seem to transcend an American history that was cruel and oppressive at critical times, and they never cease to inspire people without power to seek redress of grievances and create a system where people can enjoy their “inalienable rights” of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Bringing a Dark Chapter into the Light

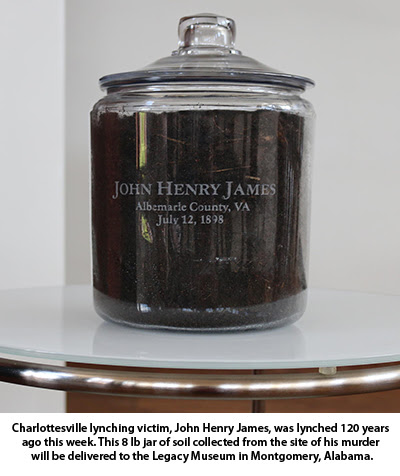

For John Henry James, the night of July 12, 1898, was not about Jefferson’s words. Charged with assault of a white woman, James was dragged off a train just outside Charlottesville, lynched by a mob, and his body was riddled with more than 70 gunshots. The perpetrators of this outrage were never identified, even though none of the mob hid their faces. This event was more than about terror for him, but a means by which all blacks could be “terrorized” and kept in their places by citizens who would hide behind the facade of southern gentility. A recent study found that there were 4,400 incidents of domestic terrorism directed at blacks between 1877 and 1950.

For John Henry James, the night of July 12, 1898, was not about Jefferson’s words. Charged with assault of a white woman, James was dragged off a train just outside Charlottesville, lynched by a mob, and his body was riddled with more than 70 gunshots. The perpetrators of this outrage were never identified, even though none of the mob hid their faces. This event was more than about terror for him, but a means by which all blacks could be “terrorized” and kept in their places by citizens who would hide behind the facade of southern gentility. A recent study found that there were 4,400 incidents of domestic terrorism directed at blacks between 1877 and 1950.

Drawing attention to these events in our history is important as we struggle to build a better future. To that end, members of the Charlottesville community conducted a “soil collection ceremony” at the site where the lynching occurred, placing the soil into a clear covered jar with James’s name inscribed, and more than 100 people have now embarked on a Civil Rights Pilgrimage that will visit civil rights sites in the south over the next week. They will transport the soil to the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, and return with a marker from the National Memorial for Peace and Justice at the conclusion of their journey. You can follow the progress of the Pilgrimage by using the hashtag: #cvillepilgrimage.

Lifting Others Up

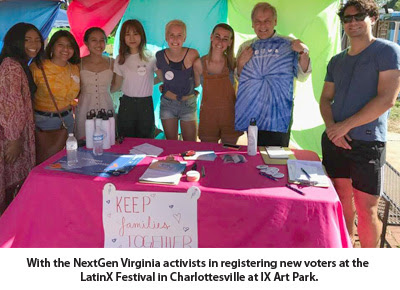

Later this weekend, Charlottesville witnessed yet another event designed to draw attention to injustice and to build hope for the future — the LatinX picnic and Harmonia music benefit for migrant families at Ix Art Park. Hundreds came for great music, food, and to raise money for a terrific cause. In our city, we are proud to show our solidarity with those who are under attack because of the color of their skin or the places from which they come, and to challenge ourselves and others to live up to American ideals.

Later this weekend, Charlottesville witnessed yet another event designed to draw attention to injustice and to build hope for the future — the LatinX picnic and Harmonia music benefit for migrant families at Ix Art Park. Hundreds came for great music, food, and to raise money for a terrific cause. In our city, we are proud to show our solidarity with those who are under attack because of the color of their skin or the places from which they come, and to challenge ourselves and others to live up to American ideals.

The Pursuit of Happiness

Americans over time have used the Declaration as a way to measure our success as a nation, as a standard to which we can all aspire. For this reason, the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” has special meaning for both citizens and their elected representatives. As historian Gary Wills so aptly describes in his book Inventing America, for Jefferson, the Pursuit of Happiness meant something beyond simply pursuing your self-interest, whether it was social, economic, or political. In Jefferson’s view, and in keeping with the philosophers whose works formed the basis of his education, the pursuit of happiness was only to be found in the exercise of a person’s virtue and his or her ability to help shape the positive experiences of other citizens. In other words, the pursuit of happiness was not only an individual right, but a collective aspiration that placed civic virtue and citizen participation at its core; citizens exercised their virtue both for themselves and by helping others. It was this “virtue” that would help us succeed as a democratic nation.

This perspective is very different than contemporary political discourse, where the focus has frequently been centered on citizens pursuing their narrow self interest. This is the guiding principle of those who begin with the free market as the basis of freedom; we realize ourselves through pursuit of self interest in the economic realm, and that quest improves the prospect of individual and collective happiness. Jefferson’s words, however, go much deeper. Pursuing “happiness” is more than just an individual undertaking. For Jefferson, there is a commonality to the political experience, and we should try to find ways of working together to make the society operate more effectively for everyone who lives within it. The common good and the civic virtue of helping others was key to the “pursuit of happiness.”

That is why both the “soil ceremony” and the LatinX events are so important. They are reaffirmations of our desires to improve the common good.

America has always been a country based on idealism and optimism. Not only are our ideas and ideals more powerful than most, but we believe we can change the world. In America, we believe that rational discourse can lead to positive change, and those of us who serve in public office hopefully embrace this view even more strongly than does the general public. For without this belief, our public service is reduced to simple and crass economic and social calculations in a cynical struggle for power that may or may not help other Americans.

The July 4th naturalization ceremony represents that idealism. For the hundreds of people from around the globe who have taken the oath on the portico of Jefferson’s Monticello, their stories are the stories of America. My great grandfather came from southern Italy in the early 1900s, arriving at Ellis Island with no ability to speak English and hardly a trade. He made his way to Upstate New York where he settled with my great grandmother and made a home for them and their children. They worked hard and participated in civic life. They made my future successes possible. In this country, we are now at a critical juncture in our history. There are Americans who would seek to create walls between others not just on the borders but within communities themselves. There are many reasons for this, some more understandable than others, though the recent efforts by the Trump Administration have strained credulity in their harshness.

This is not the first time our country has been embroiled in anti-immigrant hysteria. But, if history is any guide, Americans have traditionally risen to the challenge, fighting to tear down barriers that prevent others from realizing their dreams. Our resistance to walls is part of a uniquely American struggle for justice, and there are many successes to show for it, whether in the form of the Civil Rights Movement, the crusade for women’s equality, the efforts to ensure rights for the LGBTQ community, or the push to incorporate immigrants into our social, economic, and political lives.

America as a Mosaic

We frequently hear America described as a melting pot, but another analogy recently offered by Andrew Tisch, chairman of the board of the Loews Corporation, might be more fitting. He describes America as a mosaic, consisting of people of different cultures bound together by the cement of our founding documents and democratic institutions. Mosaics are created from brightly colored individual stones, each of which has their own character and their own beauty. In assembling the mosaic, you need an adhesive, a cement, by which you can bind the individual stones together. Those stones never lose their individual character, but they are joined together to make a more complex and beautiful pattern. In a melting pot, the individual pieces lose their identity with time to become part of the common stew. In America, however, we allow those brightly colored individual stones to shine as they are joined together in the common mosaic called the United States. Without the cement of the founding documents of our country, including the Declaration and the Constitution, and our social, economic, and political institutions, there would be very little to keep the stones together.

We frequently hear America described as a melting pot, but another analogy recently offered by Andrew Tisch, chairman of the board of the Loews Corporation, might be more fitting. He describes America as a mosaic, consisting of people of different cultures bound together by the cement of our founding documents and democratic institutions. Mosaics are created from brightly colored individual stones, each of which has their own character and their own beauty. In assembling the mosaic, you need an adhesive, a cement, by which you can bind the individual stones together. Those stones never lose their individual character, but they are joined together to make a more complex and beautiful pattern. In a melting pot, the individual pieces lose their identity with time to become part of the common stew. In America, however, we allow those brightly colored individual stones to shine as they are joined together in the common mosaic called the United States. Without the cement of the founding documents of our country, including the Declaration and the Constitution, and our social, economic, and political institutions, there would be very little to keep the stones together.

So while we have many in this country who want to continue to build walls both at the border and within communities, Jefferson would encourage us to create the new American Mosaic of the 21st Century, complete with the various talents and skills and hopes and dreams of all Americans, including new Americans who seek a new life for themselves and their families. One of the challenges for elected officials today is to determine how best to do that, and to expand the table of civic life to include more people of diverse backgrounds to strengthen the country and expand the American dream.

With all of our problems, our history shows us that it is great to be an American.