“Starving the Beast,” a film produced by Bill Banowsky and directed by Steve Mims detailing political and financial assaults on America’s system of public university education, hit theaters last month. Early reviews suggest that this is a “must see” for anyone concerned about higher education and where our country may be heading. The film provides examples, including from the University of Virginia, illustrating political attacks on institutions of higher learning and efforts to reduce funding across the country.

States are the Foundation of Public Higher Education

States have always been at the center of the promise and the problems of public higher education. Two Virginia institutions were there from the beginning. While the College of William & Mary was initially a private school founded by royal charter in 1693, making it the second oldest college in the United States, it became a public institution in 1906. The University of Virginia was chartered by the state in 1819, following numerous unsuccessful attempts by Thomas Jefferson to convince the elected leaders in the Commonwealth that a state-sponsored school separated from religious doctrine was an enterprise worth pursuing. Higher education was not only a vehicle that provided upward mobility for second and third generation Americans, whose parents worked long and hard hours for low wages, but it supplied the scientists and thinkers that still fuel the technological innovations that keep us the dominant economy on earth.

Public universities chartered by the states proliferated in the second half of the 19th century, spurred on by the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Acts of 1862 and 1890. Many of these were created with the desire to democratize higher education by making it available to citizens based on merit rather than on social class, and in hopes of finding practical applications for scientific research generated from within the university.

The real explosion in public universities occurred in the early 1900s and after World War II, fueled by demand for more education and funded partly by the GI Bill. Americans embraced state colleges funded by the public, which took the form of direct state appropriations or federal grants to returning veterans. To say this experiment in public education was successful is an understatement. America created the best educated population on earth and generated economic prosperity to match it. And state funding was essential in creating this value. During this period, great state systems of higher education were created – systems like California’s, New York’s, and Wisconsin’s. Virginia joined their ranks in more recent decades, and we now take it for granted that we are among the best state systems in the nation. But these great systems of higher education did not happen by luck. They were the product of deliberate decisions made by legislatures and academic leaders. And they can just as easily be destroyed or dismantled.

Part of higher education challenge has always been money. As public dollars became tighter in the early part of this century, greater pressures arose. Fewer public dollars meant that public universities had to raise tuition or seek private donations, or both. Each of these approaches is fraught with difficulties. Raising tuition can price student talent out of the university marketplace, including minorities and other first generation students we need for our future. Tuition increases also saddle students with so much debt that building their own wealth becomes more problematic after graduation. Finally, over-reliance on private donors creates incentives for universities to base programming on where the money comes from rather than the mission of the institution.

Recent Attacks in Other States

In Virginia’s last budget cycle, we added $300 million in funding for higher education. Other states have not fared so well. In Wisconsin, Gov. Scott Walker recently moved to cut $350 million from the state’s twenty-six campuses and weaken the university’s tenure system. Before he left office, Louisiana’s Gov. Bobby Jindal proposed $400 million in higher education cuts in a state where tuition at state-sponsored colleges had risen 90 percent during his term. Last year, the Governor of Arizona, with support of legislative leaders, proposed cutting all state support for the community college system. Kentucky’s governor, in support of his recent proposal to cut $18 million from higher education, said taxpayers should support engineering and not humanities majors. The examples go on and on.

In some states, the attacks appear more overtly political. The President of the University of North Carolina, Tom Ross, was fired in 2015, in what many described as a “political move” following Republican takeovers of the House, Senate, and Governor’s office. In Texas, University of Texas – Austin president, William C. Powers, Jr. was forced to step down by the university’s regents after he refused to embrace a series of initiatives proposed by then-governor Rick Perry.

Challenges in Virginia

Virginia has also seen its share of political controversy and budgetary challenges. Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli’s witch hunt against former U.Va. Professor Michael Mann, one of the 97 percent of all climate scientists who argue that climate change is primarily caused by human activity, provides a glimpse at the type of mischief that can be generated by overly political Attorneys General. We also experienced the firing of U.Va. President Teresa Sullivan in 2012, which was so botched and without merit that politicians of both parties came to her defense and supported her ultimate restoration. And most recently, we have witnessed the controversy over the University’s creation of a sizeable “Strategic Investment Fund,” an action which generated criticism from an interesting coalition of Republicans and Democrats who complain much about tuition increases and whether there are enough slots for the children of their constituents to gain admission to the state’s flagship institution, but say little about the level of state funding. In fact, the state has been underfunding Virginia higher education for years; university leaders at U.Va. argue that state monies presently fund less than 10 percent of its overall operating budget, and that this lack of funding is what has fueled tuition increases. While the Commonwealth’s budget writers may argue that this figure is misleading, even they admit that state support as a percentage of university expenditures has been falling, and is now less than the percentage generated from tuition.

Putting Cuccinelli’s crusade aside, the threats to the Virginia system of higher education have not been as visible as in other states, primarily because we have not had a major tax cut since 1998, when former Gov. Jim Gilmore’s car tax repeal blew a major hole in our budget. Gov. McDonnell’s “Grow by Degrees,” though not matched by serious financial investments, garnered significant support from the legislature, and there was broad bipartisan support for the higher education funding increase proposed in Gov. McAuliffe’s recent budget.

Tax Cuts Can Mean Cuts in Higher Education

All of that could change, however, with the election of a Governor supportive of tax cuts. If you look at the states where higher education has taken the greatest financial hit, almost every one was preceded by a major tax cut, which then caused a budgetary shortfall. When a state budget is squeezed, higher education is an easier target for cuts than K-12 education or health care, in part because colleges and universities have other sources of revenue, most notably tuition. Witness the most recent developments in Kansas, where Gov. Sam Brownback approved almost $50 million in higher education cuts in the aftermath of a major tax cut several years ago. This could easily occur in Virginia.

Under-Investment in Virginia Higher Education

One need only look at Virginia budgets over the last several decades to find a quiet but unmistakable under-investment in higher education. Higher education’s share of the general fund budget has declined from 14 percent of the total in 1992 to 10 percent in 2017. Our State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) reports that Virginia’s public investment has fallen, in 2014 dollars, from $9034 per student in FY 2001 to $4840 in FY 2014 (our recent budget proposed increasing this figure slightly for the next fiscal year). The trend is also prevalent at our community colleges; using 2016 dollars, the Commonwealth’s investment per student was $5550 in 2001; today, it stands at $3837. Virginia is not alone in these funding declines; only Alaska, Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming increased per-student education funding between 2008 and 2015.

The Commonwealth Lags Behind Its Stated Goal

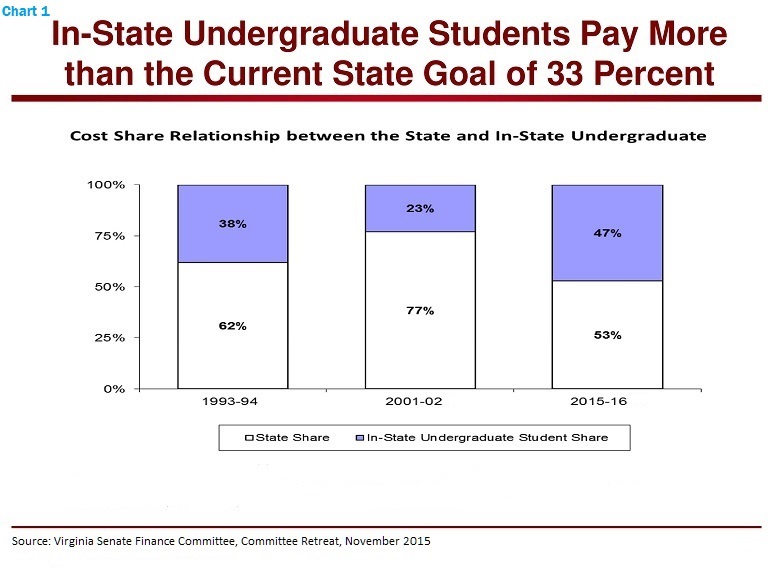

The Commonwealth’s stated goal is to fund 67 percent of the costs of education for in-state students. Yet, as shown in Chart 1 (below), the state’s share of the cost of public higher education has been declining annually since FY2002, when it paid about 77 percent of the costs, to FY2016, when it will only pay 53 percent; the portion of education costs paid from tuition rose during that time from 23 percent to 47 percent.

Again, the problem is national; the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO) reports that, nationally, reliance on tuition to fund educational budgets rose from 25 percent in 1990 to 47 percent in 2015.

SCHEV estimates it would take more than $600 million additional to reach the 67 percent policy goal, and that meeting that percentage would reduce average tuition by $2500 below current levels.

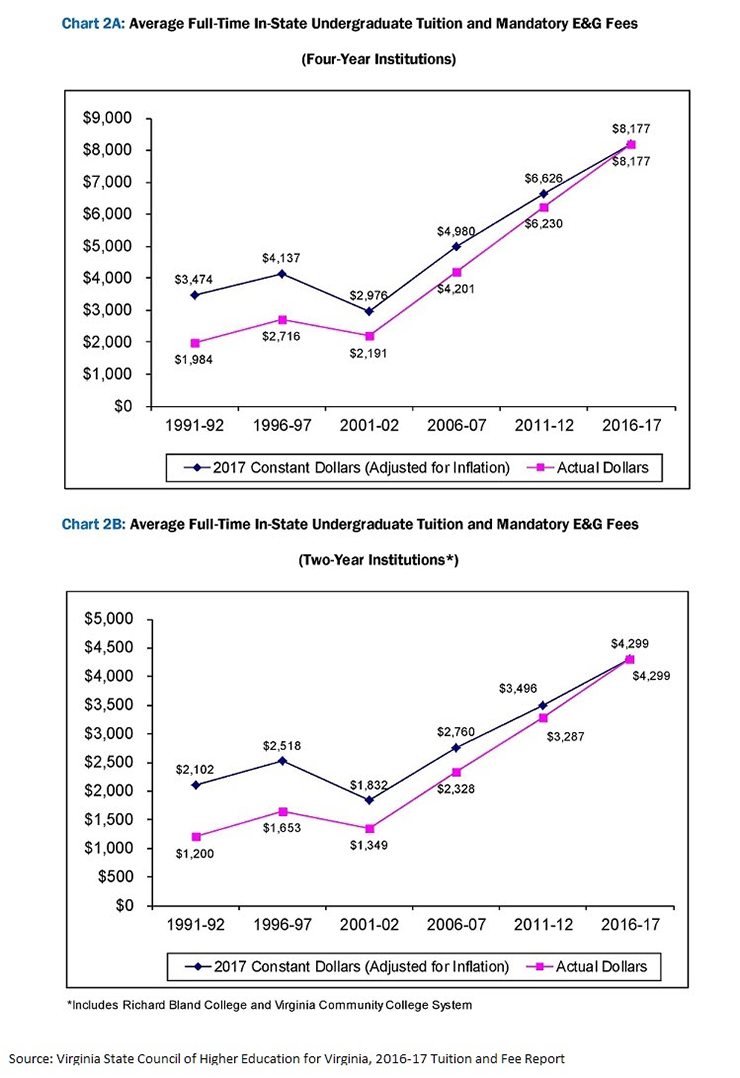

The charts below clearly show the explosion in tuition and costs in the last several decades.

As tuitions rise, so too does student debt. Demos, a think tank devoted to student debt issues, states, “Our once debt-free system of public universities and colleges has been transformed into a system in which most students borrow, in large amounts.” As of 2014, more than seven of ten college seniors have borrowed for college, with an average debt of $29,400; the Virginia figure is close to $30,000. A study by the Center for American Progress found that borrowing among Virginia families increased by 62.8 percent between 2007-08 and 2011-12, higher than the national average. SCHEV states that the average total charge for an in-state Virginia student living on campus is now 47.6 percent of disposable income, up from 31.8 percent in FY2001. These trends have the greatest impact on low- and moderate-income families. For many, this is putting the American dream of a college education increasingly at risk; for others, the degree of debt means postponing major financial decisions such as buying a home or investing in a business. This has serious potential economic impacts for the next generation and the strength of the economy.

Virginia – Different from Other States

Higher education in Virginia, especially among its tier-one institutions, is organized somewhat differently than in other states. First, the Commonwealth was among the first states to provide significant autonomy and budgetary control to our universities. This has permitted these institutions to set their tuition rates and provided them freedom from certain procurement requirements applied to other state agencies. Second, U.Va., beginning under President John Casteen, has been relentlessly successful in building its private endowment, providing it with the funds to build academic excellence in ways it could not had it relied solely on state appropriations. It also meant that it could continue to enroll a diverse student body from across the country who would pay tuition substantially higher than Virginians, a development that not only increased the stature of the university, but increased its endowment substantially (almost 70 percent of total private donations to U.Va. come from outside the state). Legislators are justifiably proud of this flagship institution, so much so that they continually press for it to create more slots to permit the children of their constituents to gain access.

Nonetheless, the recent controversy over U.Va.’s “Strategic Investment Fund” shows that this fragile “consensus of support” could erode at any moment, and the debate exposes some of the underlying tensions in a higher education funding model that is becoming increasingly unsustainable. Ironically, the financial tensions are more likely to manifest themselves within state institutions less wealthy than U.Va.; when state support declines, these institutions have less flexibility to make up the difference in ways other than cutting faculty and staff, increasing class size, raising tuition, reducing student aid, neglecting physical and intellectual infrastructure, or all of the above.

Future Challenges – What is to be Done

As budget pressures increase, more pressure will be placed on higher education. And while it is true that our public colleges and universities will need to make changes and reduce costs, Virginia will lose its competitive edge, and our students will enjoy less opportunity, if we fail to invest adequately. So what is to be done?

First, the Commonwealth should continue its strong tradition of encouraging academic freedom free from political interference. Our institutions should be operated by strong academic leaders who understand education, encourage innovation, and find ways for the universities to enhance the private sector. That is the essence of what makes Virginia’s higher education system strong.

Second, the legislature should adopt a five year program to increase state appropriations to meet our stated goal, to finance 67 percent of the costs to in-state students attending Virginia’s colleges. We have embraced this goal in numerous budgets and it is supported by SCHEV and other advocates of higher education; now, we need to fund it.

Third, the legislature should invest more in student aid to make colleges more affordable and accessible. In this two year budget cycle, we earmarked almost $50 million to the Virginia Student Financial Assistance Program (VSFAP) to provide student aid. We should double that investment. If we are to carry out the vision of the “Grow by Degrees” initiative to increase the number of Virginia graduates, we need to encourage students who might not have considered community or four-year college due to finances to realize that we can help with financial aid.

Fourth, the Commonwealth should do what it can to assist Virginia graduates in refinancing their present debt and make it easier for them to buy homes, invest in businesses, and participate in the American dream. One idea proposed by Del. Marcus Simon (D – Falls Church) to use our bonding authority to assist in the refinancing of student debt is worth careful consideration.

Improving higher education is not just about investing more money. But our challenges cannot be met – and the New Virginia Economy cannot be fueled – without investing the funds necessary to maintain Virginia’s higher education system as the best in the world.