On December 31, 2019, a brief release appeared on the website of the World Health Organization (WHO). Captioned “Pneumonia of unknown cause – China,” it briefly reported about a number of cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology (unknown cause) detected in the city of Wuhan, a port city of 11 million inhabitants. Few in this country took note, with the notable exception of scientific specialists in the areas of infectious diseases and public health.

Halfway around the world, Governors and state legislators were preparing for their annual legislative sessions. Virginia was among the first of the states to convene, and they did so on January 8. Major changes were contemplated for the state, since the Democrats had just taken control of the legislature and held the Governor’s office as well. On the other side of the country, Washington state convened its own session on January 13. Both states were making history as each elected their first women Speakers in history — Eileen Filler-Corn in Virginia and Laurie Jinkins in Washington. And Democratic Governors Jay Inslee of Washington and Ralph Northam were optimistic about making their marks on their states in light of a strong economy and Democratic majorities. Within two months, they would join other Governors across the nation, as they confronted the greatest challenges of their administrations, and their states would be plunged into the most serious crisis since the Great Depression.

Like much of the public, few state lawmakers noticed when the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued a travel warning advising against any nonessential travel to China on January 6, or when the virus began to affect other countries. Legislators in both Virginia and Virginia were focused passing their agenda –gun safety legislation, expanding the minimum wage, energy transformation, and redistricting reform. Neither legislature seemed worried about COVID-19. That attitude, however, changed quickly in the Evergreen state; with its closer ties to China and the far east, the report that 35-year-old Washington man had tested positive for COVID 19 after returning from Wuhan appeared ominous. By the end of February, Washington had reported 2 deaths, and was becoming a “hot spot” for the growing number of cases reported throughout the United States. On February 29, 2020, Washington Gov. Inslee, at the instigation of public health officials, declared a state of emergency. COVID-19 had been unleashed upon America.

Washington’s new House Speaker, an attorney who had worked in health care for years, including a stint in the executive branch, understood immediately the implications of the disease for her constituents and the state, and was an immediate supporter of the Governor’s action. “When we looked at the data, it was clear that we had no choice but to get ahead of the curve by encouraging social distancing,” she explained. “We also had to do some education; some of our members initially viewed this as a ‘hoax.’ Fortunately, our minority leader stepped up, stating that the data was there to support decisive action.”

In early January, as both legislatures met, the WHO sent directives to hospitals around the world suggesting immediate action to control the virus. Since there was no vaccine, the purpose of the warning was to prevent the spread of the virus, complicated by the fact that many “carriers” were asymptomatic and therefore did not realize that they were putting others at risk. On January 15, an emergency committee of international experts met in Geneva to assess whether the outbreak constituted an international emergency. The same day, crowds cheered as the Virginia legislature ratified the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), becoming the 38th state to do so.

A Growing Concern

By the February midpoints of the legislative sessions in Washington and Virginia, a full-scale epidemic was underway in China, and cases were being reported in places as diverse as Iran and Italy. South Korea had initiated a massive testing program and Singapore was vigorously engaged in fighting the spread of the virus.

The spike in Italian cases did not occur until early March, and thoughts of a pandemic had not seriously crossed the minds of many state lawmakers, especially in the Commonwealth, which seemed so far away from China and even Washington state. Some Virginia public health officials, however, were growing increasingly concerned. Dr. M. Norman Oliver, the Commissioner of Public Health, and Dr. Lilian Peake, the state epidemiologist, appealed to Northam, himself a doctor, to act. Despite the lack of one reported case, Gov. Northam wanted the Commonwealth to be ready. On March 3, he informed the public about the state’s plan, attempting not to frighten citizens before the threat was clear. It would not take long for the fear to materialize.

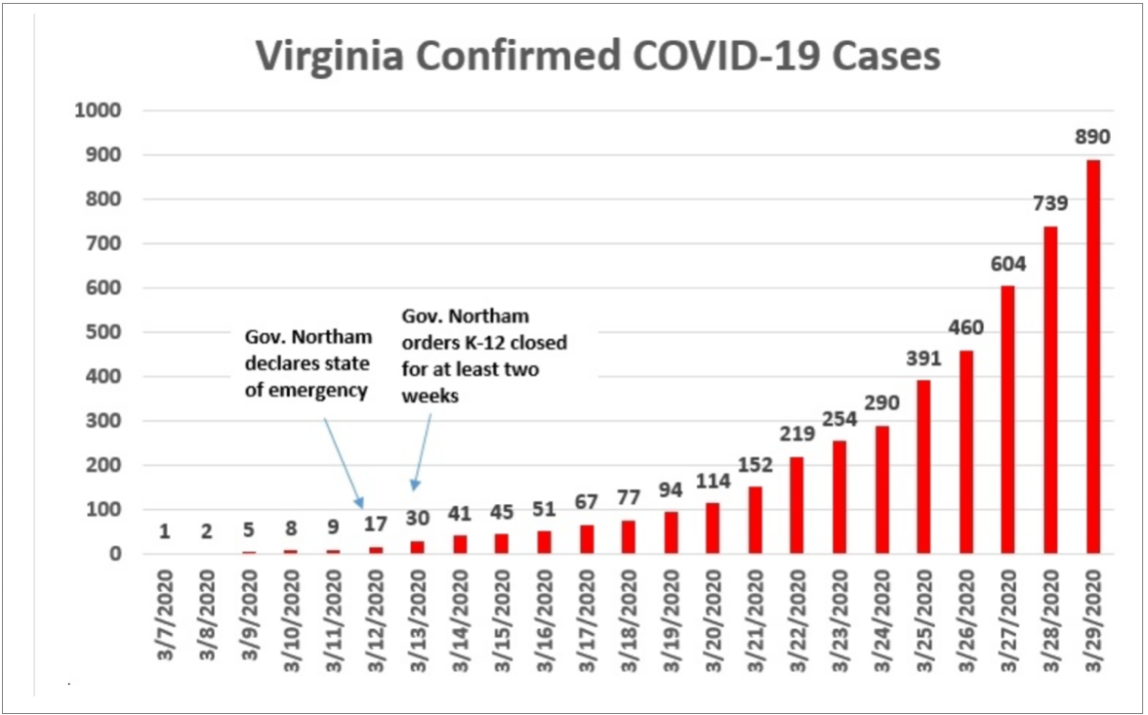

On March 10, 2020, after the COVID-19 viral disease had swept through at least 114 countries and killed more than 4,000 people, the World Health Organization formally labeled it a pandemic, the first use of the term since the 2009 H1N1 “swine flu” outbreak. The Virginia legislature was about to pass its two-year biennial budget; it was a time when most lawmakers were scurrying to push their respective bills over the finish line for passage and looking forward to adjournment. While they were now aware that Virginia had reported its first case of COVID-19 on March 7, they were up against the constitutional deadline for producing a budget. The hope remained that “it can’t happen here.” On March 12, they finished their work and adjourned.

Like Virginia, the Washington state legislature was preparing to adjourn on March 12, but in a very different environment. As of that date, the state had confirmed 457 cases across 13 counties, and recorded 31 deaths linked to the virus(as of March 27, Virginia had 17). Before adjourning, lawmakers gave Inslee budgetary authority to send $200 million for assistance to the public and rural hospitals. Inslee had just issued a new order preventing gatherings of 250 or less in the most affected counties. He then ordered the closing of the schools in those areas. It was only the beginning.

Ignoring the Scientists

The Trump administration largely ignored the warnings. On Jan. 22, asked by a CNBC reporter whether there were “worries about a pandemic,” the president replied: “No, not at all. We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control,” and Larry Kudlow, the President’s Chief Economic Advisor, stated in late January that the virus would have “minimal impact” on the U.S. economy. Even after the Federal Reserve Board said the effects “could… spill over to the rest of the global economy, and the warnings of the CDC” Kudlow persisted: “I don’t think it’s going to be an economic tragedy at all,” he proclaimed. State Governors knew better and could no longer wait for a federal response.

Flattening the Curve

State Governors possess extraordinary emergency powers, and began using them. Emergency declarations permit governors to mobilize the National Guard, close schools, invoke curfews, and prevent gatherings. They allow states to redirect health care workers to where they are needed and organize hospitals to meet the demands of an outbreak. They can seize properties to create emergency medical centers if hospital beds are not available. They can impose quarantines. And it now appeared that they would use every tool at their disposal.

With the federal response lagging, the action would be in the states. The mobilization against the virus involves local and state health departments, state emergency preparedness offices, and state and local first responders, all of which are under the control of individual states. Most of the testing would likely be coordinated through state auspices, even if the federal government eventually stepped up to provide the kits. And finally, coordination of hospital beds, which were threatened to be overrun with virus cases, is largely a state responsibility. If there was ever an argument for “why states matter,” this was it.

From the first recognition of the crises, most Governors, independent of party, knew that the best prospects for confronting the virus involving “bending the curve” of transmission. Use of the term “social distancing” became commonplace, as chief executives first implored, and then compelled, citizens to remove themselves from extensive contact with others. New York’s Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency on March 7, and then deployed the state National Guard to New Rochelle, a small community north of New York City, to enforce a 1-mile “containment zone” in response to a sharp uptick in cases. On March 12, he effectively shuttered Broadway with his prohibitions of gatherings over a certain size. New York was about to pass Washington state in reported COVID-19 cases, and Cuomo was asserting control. “Be upset at me,” he said. “The buck stops on my desk. I assume full responsibility.”

Cuomo and other Governors were now seeing exponential increases in the reported cases that appeared eerily similar to the trajectory in Italy, and felt compelled to act. On March 17, Texas Governor Gregg Abbott joined 20 other state Governors, including those in California, Florida and Arizona, in mobilizing the National Guard. By March 20, 2020, 45 states had closed all or a portion of their schools; this meant that at least 118,000 U.S. public and private schools were closed, affecting at least 53.7 million school students. Several state Governors cancelled their presidential primaries, with Ohio Governor Mike DeWine doing so the day before voting. On March 19, Gavin Newsom, the Governor of California “shut down” the most populous state in the nation by directing residents, with certain exceptions, to remain at home, affecting not only 40 million inhabitants, but an economy which is 6th largest in the world. Even state legislatures adjourned or suspended their sessions in response to the crisis. By March 20, 20 legislatures had either postponed, suspended, or adjourned their sessions due to the outbreak. It would fall mainly to Governors to manage the crisis.

Hobbesian Choices

For the most part, the public has backed the action of state Governors. The words “flatten the curve” are heard and seen everywhere, from internet sites to billboards to Barack Obama’s twitter posts. But to say that it has been an easy choice for states to curtail business with stay-at-home edicts is simplistic at best. Although Governors clearly understand the public health rationale for keeping citizens at home, they are also mindful of the economic impacts of such plans. There are significant political and ethical dilemmas for chief executives worried not only about the curve which represents the spread of the virus, but the downward spiral of their economies without the influx of dollars which flow from employment and economic activity. When people do not work, and businesses are not open, families are left with fewer resources to buy food and pay their bills. And the state government is not receiving the revenue necessary to pay for schools and key services. When Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak imposed a month long freeze on gambling in mid-March, he was undoubtedly cognizant of how his action would affect an industry that fuels the state’s tourism and hospitality-powered economy. It was a risk he was willing to take, because the alternative appeared much worse. Similarly, Governor Cuomo, while acknowledging his state’s economy was taking a hit, has placed health concerns above all else. Announcing the shutdown of all non-essential services in the state on March 20, he explained, “I want to be able to say to the people of New York — I did everything we could do….“And if everything we do saves just one life, I’ll be happy.”

Governors around the country are struggling to find the appropriate policies that keep some level of economic activity while flattening the curve of infection. They will continue to do so if only because they will eventually have to decide when to relax some of the most severe measures. Some, including Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Kate Brown of Oregon, Ralph Northam of Virginia, and Jay Inslee, had not yet issued stay-at-home orders, even as they left open that possibility. As they do, they also they are also understanding the impacts on their state economies and budgets. All are working feverishly to bend the curve, relaxing testing requirements so that medical providers and first responders would know whether they had the virus, collecting and distributing masks and protective gear, and planning to expand hospital capacity to address a potential surge in patients. Nonetheless, the states are feeling the economic impact; n Washington state, Employment Security Department commissioner Suzan LeVine reported that “[t]his week, every day, the new claims we are receiving are at the level of the peak weeks during the 2008/2009 recession. “Virginia unemployment claims in the week of March 16 were greater than for all of 2019, and the Governor’s economic advisors were warning of a massive downtown in state revenues in the 2nd quarter, a fact that would undoubtedly force major budget cuts.

Life Takes Precedence

Governors have substantial power– and all realize the choice; flattening the viral curve will almost certainly make the economic curve steeper. And most have chosen efforts to save lives, heeding the advice of National Institutes of Health’s Dr. Anthony Fauci, who recently stated “Some will look and say, well, maybe we’ve gone a little bit too far,” he said. [But] when you’re dealing with an emerging infectious diseases outbreak, you are always behind where you think you are if you think that today reflects where you really are.” As Northam put it in a media briefing on March 22, “this is a health crisis and we will be dealing with this for months, not weeks. Our economy will be stronger as soon as we get this health crisis under control.” Our economy will be stronger as soon as we get this health crisis under control.”

By March 29, the COVID-19 case reporting curve in Virginia was bending upward; 890 cases had been reported in the Commonwealth, and 22 had died from the disease. By contrast, in Washington state, the Department of Health announced the adding of 1000 cases on March 28, bringing the state’s total to 4310, including 189 deaths, undoubtedly a reflection of the earlier appearance of the virus.

Coming Confrontation with Washington

Throughout the month of March, the public was treated to daily press briefings from the White House illustrating frequent differences of opinion between Trump and the scientific experts as well as foreshadowing an emerging political and legal confrontation between the President and state Governors. By contrast, the daily press briefings of New York Governor Cuomo, with their combination of empathy, scientific information, and warnings had become “must see TV” for those starved for leadership at the federal level. Trump’s proclamation that he “ would love to have the country opened up and just raring to go by Easter” roiled Governors as they witnessed exponential growth in cases in their states and saw dire forecasts of what might be coming. Sophisticated modeling at the University of Washington, for example, was predicting that Virginia would experience its peak impact of cases and demands for hospital beds in early May, even with all the regulations remaining in place; because Washington state began prohibitions earlier, its peak was projected for mid-April, and its death toll would be marginally less than the Commonwealth’s. Governors were increasingly concerned about their state’s resources being overtaxed and whether federal help would be available in a coordinated fashion. They were also worried that relaxing regulations in one state might allow the spread of the virus into their own. “The patchwork remains a patchwork as long as the federal government doesn’t step up and recognize this is a war,” Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker argued. “The federal government needs to lead and until it does, we will be a leader here in Illinois.”

Regional efforts continued to increase coordination and consistency across state lines. In late March, Connecticut, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania coordinated their regulations regarding the closure of bars, movie theaters, malls and bowling alleys, all in an attempt to avoid a patchwork of prohibitions. Many observers speculate on what will occur if Trump attempts to “reopen America,” whether it occurs at Easter or at some other time. He may be met, at least in some sections of the country, by massive disobedience, especially if the death toll continues to rise precipitously. More significantly, it is not clear what power he has to force relaxation of state prohibitions. Governors appear to have the constitutional powers to impose these rules and, absent the President withholding certain types of aid from states who fail to comply with his edicts, it is unclear what he can do. We may be headed toward this confrontation, the results of which may determine the extent to which states matter.